The Brothers’ Grip

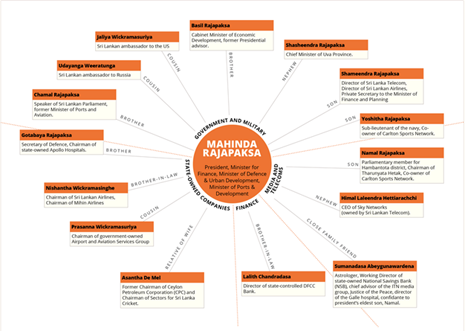

In Sri Lanka, power is concentrated – around President Mahinda Rajapaksa. Meet his brothers, sons, other relations and even his astrologer-turned-banker.

By Eric Ellis

Ishara S.KODIKARA/AFP/Getty Images

The President’s brother, and Sri Lanka’s Defence Secretary, Gotabaya Rajapaksa inspects a guard of honour during an April civil-war commemoration ceremony.

Meet Sumanadasa Abeygunawardena. He’s every saver’s dream come true – a bank director who can predict the future.

Abeygunawardena is the ‘working director’ of one of Sri Lanka’s biggest banks, the state-owned National Savings Bank (NSB) – that is, when he’s not being a celebrity soothsayer.

Abeygunawardena’s main claim to fame in Sri Lanka is as an astrologer. With his columns in government-friendly newspapers, a regular star-gazing spot on national television and a lucrative personal horoscope service delivered via SMS with the state telco, he’s one of the country’s most visible faces.

Eric Ellis/The Global Mail

Celebrity soothsayer and power-banker Sumanadasa Abeygunawardena, relaxing after the President’s visit to open his new astrology centre.

“World renowned” Abeygunawardena had no formal experience in banking before his “close family friend” Sri Lanka’s President Mahinda Rajapaksa – who is also Finance Minister – tapped him for the NSB board in 2007.

That was the year before the world’s financial system melted down, when a judicious bit of fortune-telling could have come in handy, for bankers and investors alike. Unfortunately, Abeygunawardena’s astrological skills didn’t seem to do NSB much good that year – profits fell by 32 per cent as times got very tough for bankers everywhere.

But what perspicacious predictions this seer has made elsewhere.

In mid-2008, Abeygunawardena says he “convincingly predicted” Barack Obama would be elected American president later that year. No matter that the signs were clear to many: the United States economy then managed by Obama’s opponent President Bush was near collapse; Obama had just swept the Democratic convention; and he was belting Bush in opinion polls. These are but trifling details when one is seeking to maintain a reputation as a fortune teller in a land obsessed by astrology.

“It is not easy to make such predictions,” Abeygunawardena told a Sri Lankan newspaper a year later, after Obama was installed in the White House.

“You have to study their horoscopes thoroughly, but that alone won’t do…it also requires a high degree of psychic powers.”

He again demonstrated his gift in May 2009, when he predicted the defeat of the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka’s long-running civil war. By then, the Tigers had been reduced to a handful of diehards defending a beach relentlessly pounded by the Sri Lankan military, which had progressively taken the Tigers’ once impregnable strongholds over previous months.

Still, a prediction is a prediction, and Abeygunawardena was again proved right a few days later when the Tigers’ leaders were killed and the fighting was over. He promptly predicted the triumphant President Rajapaksa would be re-elected, as he duly was in the khaki poll called in the triumphant wake of the Tigers’ defeat.

Though many commentators and analysts may have arrived at projections similar to those of Abeygunawardena – and even before he made his calls – such an oracle is obviously useful as the steward of a prestigious bank that finds itself constantly buffeted by unexpected events. The shareholders of America’s Citibank and Lehmann Brothers, and Britain’s Lloyds and Northern Rock might well lament not having had such a ‘master of the universe’ to guide them through torrid market events.

Despite a steep fall in profits, NSB didn’t go under, as did so many banks elsewhere. However, economists argued that that had more to do with Sri Lanka’s isolation from the world’s economic mainstream, than with how the bank was directed.

Profits improved but NSB was found wanting for some mystic perspicacity again in 2012, when it was engulfed by scandal after a business deal that went wrong. Did its astrologer-director Abeygunawardena see that coming? It seems not; bank profits fell, again by a third.

All the while, Abeygunawardena seems to be making good use of his powerful connections. To set up delivery of his ‘My Astro’ daily horoscopes via SMS, he teamed up with state telco Sri Lanka Telecom, where President Rajapaksa’s nephew Shameendra is a director.

The Global Mail visited Mr Abeygunawardena in July this year, in the southern city of Galle, just as President Rajapaksa was arriving to publicly open his celebrity friend’s commodious new library and ‘astrological centre’.

It was a splendid occasion, as southern Sri Lanka’s Sinhalese establishment stepped out in their finery to welcome their favorite son of Ruhuna – the ancient Sinhala kingdom of these parts – to his heartland.

A new road had just been laid to the Abeygunawardena compound, to ease the passage of the presidential carriage. But tarmac takes time to set in the tropics, and it played havoc with the high heels and sandals of Galle’s great and good. Still, villagers beyond the Abeygunawardena fortress were happy enough about the Rajapaksa visit – they haven’t seen a tarred road in their village for years.

Ishara S.KODIKARA/AFP/Getty Images

Blood brothers: Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa with his brother, Defence Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa, in the background.

President Rajapaksa declined to be interviewed at the event so we return the following morning to talk to Abeygunawardena himself. He is sitting in his courtyard behind three-metre walls. His security shoos us away, but when he sees white faces he calls off the muscle. “Let the suddo in,” he barks, using the Sinhala pejorative for foreigner.

Bald, bare-chested and barefoot, he’s clothed only in a brown sarong, kicking back in an armchair, taking in the morning cool. Minions fuss around him, plying him with tea and phones as well-wishers call to rhapsodise about yesterday’s pageantry. “Big house, big house,” he boasts, pointing at his newly built five-storey pile, clearly the largest and most lavish in the hamlet. But as impressive as the house is, it’s hard to look past its owner’s bling. Abeygunawardena’s fingers, wrists and neck drip with gold jewellery, and he’s quite keen to show it all off to the visiting suddo.

He beckons me to reveal my palms, as if to read them, while running through his CV: NSB director, chief advisor of local ITN media group, justice of the peace, director of the Galle hospital, and confidante to the president’s eldest son, Namal, who had swung by the previous night for a meal and counsel. “He will be the president in 10 years,” predicts this soothsayer.

But it’s clear the incumbent is his main interest, and Abeygunawardena beams about yesterday’s presidential patronage. “Wonderful, wonderful …” he gushes. “President Rajapaksa is a very honest man, a very lucky man.”

Many Sri Lankans would disagree. Take the Tamil activist and academic, Jaffna lawyer Kumaravadivel Guruparan, for example, who says Abeygunawardena is “good evidence of the nepotism at work”.

Abeygunawardena may have lacked banking qualifications when the president anointed him to help run one of the state’s banks, but there’s nothing in the laws of Sri Lanka’s central bank that prohibits cronies or astrologers from taking up directorships.

There is, however, a provision that prevents convicted criminals from serving on bank boards. Yet, this doesn’t seem to have discouraged another controversial Rajapaksa appointment to a government-connected bank; that of the president’s media guru Lakshman Hulugalle as a director of the Commercial Bank of Ceylon.

For most of the civil war, the Tamil Tigers triumphed in the propaganda war over the Colombo government’s hapless military. In 2006, the Rajapaksas tapped Hulugalle, a hotel trainee-cum-political advisor, to set up the Media Centre for National Security, which centralised the state’s official message to counter the Tigers’ sophisticated information apparatus.

This was part of the government’s new multi-pronged hearts-and-minds campaign against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), and it worked. As the Tigers progressively lost military ground, the government was quick to trumpet its successes, which boosted the morale of troops who’d previously regarded the enemy as having almost mystical powers. Hulugalle was rewarded by Rajapaksa, who appointed him to a succession of state boards; in 2011, for example, he was tapped to represent the state’s 10 per cent stake in ComBank.

However, Hulugalle had been convicted in 1989 by the Colombo High Court for his role in a timber scam. He was sentenced to two years in prison, a term which was suspended for 10 years. Section 42 of the country’s Banking Act disqualifies any person who “has been convicted of an offence involving moral turpitude and punishable with a term of imprisonment” from serving as a bank director. Although it was widely known that Hulugalle had a conviction against him, he was entrenched in government and appointed to the ComBank board before it was raised. Earlier this year Hulugalle tried to quash the issue by claiming – in a soft-focus interview in a government-friendly magazine – that his conviction had been due to a power struggle between party factions, and that it had later been annulled. Neither Hulugalle nor the Central Bank of Sri Lanka responded to questions from The Global Mail.

CRONYISM AND CONFLICTS abound in the Rajapakas’ Sri Lanka Inc.

Take Dhammika Perera, permanent secretary of the Ministry of Transport. That’s a powerful executive position of a key ministry that regulates one of Sri Lanka’s most pressing concerns, and which is enjoying a boom in post-war infrastructure development. Perera took this job after a stint chairing the government’s Board of Investment (BOI), which regulates investment on the island.

Though his calling card might say bureaucrat, Perera is better known as Sri Lanka’s casino king. The self-made Perera based his fortune on slot machines, then parlayed his prowess at gambling into casinos and banking. Today he is one of Sri Lanka’s richest men, controlling around 10 per cent of the companies listed on the Colombo Stock Exchange, several of which have direct interests in the transportation sector – which is regulated by the transport ministry he helps to run.

Ishara S.KODIKARA/AFP/GettyImages

Sri Lanka rugby captain Yoshitha Rajapaksa practicing in Colombo. The president's eldest son, Namal Rajapaksa, is leading a push for rugby’s revival, bringing sport stars from England, South Africa, Fiji, the US and New Zealand to prepare a Sri Lankan team that can qualify for the 2019 World Cup in Japan.

It doesn’t take long when doing the rounds of Sri Lanka Inc to bump into a Rajapaksa relative either. In the lobbies of Colombo’s business-friendly hotels, potential big-ticket investors complain that it’s virtually impossible to pursue deals without some sort of contact with – and the necessary approval from – the president’s influential brother Basil, who is Minister for Economic Development.

The president’s rugby-playing sons Yoshitha and Namal have also enjoyed a meteoric rise in business. Last year Sri Lankan cricket authorities confirmed what many in Sri Lankan media had suspected, that a come-from-nowhere TV sports channel, Carlton Sports Network, is owned by the two Rajapaksa lads.

Carlton was formed in 2011, pitching itself as Sri Lanka’s only dedicated sports TV channel. Its chief executive is Nishanta Ranatunga, brother of Arjuna, who led Sri Lanka to its greatest ever sports triumph – the 1996 World Cup cricket win over Australia. In a country obsessed by cricket, Nishanta is also secretary of the peak administrator of the sport, Sri Lanka Cricket (SLC).

Cricket in Sri Lanka has long been broadcast by the multi-lingual state broadcaster Rupavahini, to be viewed by as many Sri Lankans as possible. But last year, when SLC was offering the TV rights for the sport, Rupavahini didn’t bid for them. So the lucrative rights were won by the politically connected Carlton, which has since expanded into rugby, another very popular sport on the island.

(In early August, Carlton broadcast a rugby tournament in Galle, which had been organised by Namal’s mass youth movement, Tharunyata Hetak. The delighted Namal played in some of the matches, and even tweeted about his encounter with the tournament’s special guest, former Australian Wallabies captain, Stirling Mortlock.)

Elsewhere, the president’s cousin Prasanna Wickramasuriya chairs the government-owned Airport and Aviation Services group, which operates the island’s main airport in Colombo. It’s an important job, but Wickramasuriya has an even more challenging brief. That’s because he’s also in charge of the new Chinese-built airport in his presidential cousin’s home region of Hambantota.

Paula Bronstein for The Global Mail

Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport in Hambantota has a brand-new main terminal and big ambitions, if not yet big traffic.

Named after the president, Rajapaksa International Airport at Mattala, outside Hambantota, is a facility that redefines the word ambitious.

Designed to handle six million passengers annually, on some 75,000 flights, it has some way to go before it meets such projections. The day The Global Mail stopped by, official schedules showed 16 departures for the entire week and just three on that particular day – to Colombo, Shanghai and Dubai – and another flight the next day, ferrying Sri Lankan labourers to Dubai.

All of which might explain why the occasional bustle around the airport is not created by passengers busying through customs and immigration, but by excursion groups of local schoolchildren, marveling at the modernity. The Gulf-based budget carrier Air Arabia was lured into flying here, only to shut down its service to Sharjah after a few weeks due to a lack of passengers.

Still, there’s nothing like hope to sustain a presidential vision. Local media was recently moved to say the airport would “match Gatwick soon”, while the airport’s boss, Wickramasuriya, the presidential cousin, reportedly sees only success for the new airport and its sound business model. But after the failure to reach the opening year’s traffic targets, the latest plan is to transform the president’s eponymous airport into a maintenance centre.

One of the president’s brothers-in-law, Lalith Chandradasa (married to Preethi Rajapaksa, one of the president’s three sisters) is another ubiquitous presence in corporate Sri Lanka. He holds a directorship of another state-connected financial institution, DFCC Bank, is a former chairman of the national ports authority, and is also a director of Sri Lanka’s main corporate regulator, directors of which are appointed by the finance ministry – which is of course run by the president.

The president’s nephew Shameendra Rajapaksa also wears numerous hats, private and state. For example, he’s now private secretary to the Minister of Finance and Planning (his uncle, President Rajapaksa), but was previously private secretary to the Minister of Ports and Highways (also Uncle Mahinda).

Brother Shasheendra is another advisor to his presidential uncle, aside from his elected job as chief minister of Uva Province in Sri Lanka’s central highlands.

When he’s not attending to his various ministries, Shameendra is also a director of state-owned Sri Lanka Telecom; and of SriLankan Airlines, the chairman of which is Nishantha Wickramasinghe, another of President Rajapaksa’s brothers-in-law, who was appointed to the position despite having no previous experience in the aviation sector.

A tea planter by trade, Wickramasinghe also has a job ahead of him at the state-owned flag carrier. Despite a post-war boom in tourist numbers to the island, SriLankan Airlines lost LKR17.18 billion ($A143.6 million) in its most recent financial year on chairman Wickramasinghe’s watch.

Wickramasinghe is also chairman of Sri Lanka’s other airline, the budget carrier Mihin set up by President Rajapaksa’s brother Gotabaya, Sri Lanka’s defence secretary and mastermind of the 2009 military triumph over the Tamil Tigers. It’s also named after President Rajapaksa (Mihin is the diminutive of Mahinda) and is one of four airlines that flies to the new airport in Hambantota, making the president perhaps internationally unique in terms of political cults of personality, in having an airline and an airport named after him. Indeed, presidential fealty in Sri Lanka goes a step further, with passengers able to buy their Mihin air tickets to the eponymous Hambantota airport with 1,000 rupee notes bearing the President Rajapaksa’s triumphant image.

Through much of the 2000s, SriLankan Airlines (SLA) was a joint venture with the Dubai-based carrier Emirates, which owned 43 per cent of SLA and managed the flag carrier. But an incident in 2007 led to a permanent schism between the two airlines, and provided a revealing lesson to foreign investors.

In December that year, President Rajapaksa’s second son Yoshitha was graduating from the British Royal Navy’s officer training school at Dartmouth in Devon. Executives of the then Emirates-managed SLA had long been aware President Rajapaksa would be attending Yoshitha’s passing-out parade, and planned accordingly, anticipating that the state entourage would require seats for the presidential return to Colombo. The graduation was close to the busy Christmas period and, as one of SLA’s foreign managers tells it, the airline sent repeated reminders months in advance to the presidential palace to confirm the number of seats required and the dates, so SLA could block them from sale.

These requests went unheeded, and SLA flights from London became filled with normal paying passengers. In mid-December, the airline suddenly received a demand from the president’s office for 35 seats at the front of the plane. But by then, the flights were full and fulfilling the official demand would have meant offloading paid bookings in peak season. SLA offered seats for the president and his immediate family, but apologised that it couldn’t seat the rest of the Rajapaksa entourage.

In Sri Lanka it doesn’t do to deny the Rajapaksas, and they were furious. The offer of three family seats was rejected, and the Rajapaksa-controlled Mihin Air despatched an empty plane to London to collect the presidential party. On the Rajapaksas’ return to Colombo, Peter Hill, Emirates’ then country manager who was seconded to manage SLA, had his work permit immediately revoked; the coup de grace was administered by Rajapaksa crony Dhammika Perera, the businessman who then ran the government’s investment gatekeeper, the BOI. That is, when Emirates’ management contract at the airline expired three months later, it wasn’t renewed. Two years later, Emirates sold its stake in SLA.

Still, the flag carrier’s change in ownership seemed to come in handy a few years later for Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the president’s much-feared brother and former soldier who had reportedly turned a former career toiling in a Californian convenience store into a new role as Sri Lanka’s Tiger-toppling military supremo.

Ishara S.KODIKARA/AFP/Getty Images

Former Sunday Leader editor Frederica Jansz, pictured in 2012, feared for her life after threats over the newspaper’s coverage of the Rajapaksas. She successfully sought asylum in the US, after her claim was rejected in Australia.

LAST YEAR, ONE OF SRI LANKA’S most celebrated journalists Frederica Jansz, editor of the Sunday Leader, then one of the last independent newspapers on the island, got a tip that an SLA flight to Colombo from Zurich had been changed from an Airbus A340 to a smaller A330 – bouncing 54 paying passengers – so that the SLA pilot boyfriend of Gotabaya’s niece could personally fly a Swiss puppy home for her uncle.

Jansz telephoned Gotabaya on speaker phone and recorded the conversation. Gotabaya confirmed the story as if such things were commonplace, but when she pressed him he flew into a rage, threatening Jansz and telling her she would be killed if she published the story, which she did, the following Sunday.

A month later, a Rajapaksa crony Asanga Seneviratne unexpectedly bought the Sunday Leader, and promptly sacked her as editor. Jansz then received a succession of death threats and, fearful for her life, applied for sanctuary in Australia. She was unsuccessful, despite strong evidence in favour of her case.

In 2009, Lasantha Wickrematunge, Jansz’s predecessor as editor of The Leader, had been murdered, gunned down on a busy Colombo street. A giant of Sri Lankan journalism, Wickrematunge had written in his paper just days earlier that he would be killed by the government.

But none of that history seemed to convince the then Gillard government, anxious to curry favour with the Sri Lankan government over the procession of Tamil asylum seekers making for a new life after a brutal war. Canberra denied Jansz’s visa application, claiming that she did not face persecution. Jansz went instead to the US embassy and today lives in exile with her children in a town outside Tacoma.

Ishara S.KODIKARA/AFP/Getty Images

Gotabaya Rajapaksa and his military chiefs enjoy a Victory Day parade rehearsal in Colombo in May, which is War Heroes month in Sri Lanka. The 2009 military defeat of the Tamil Tiger rebels ended the 37-year long separatist conflict but it’s never forgotten.

UNDER GOTABAYA RAJAPAKSA’S stewardship, the Sri Lankan military is itself developing an extensive business empire. Indeed, Gotabaya seems to enjoy dabbling in corporate matters. When he’s not managing the military, he’s also chairman of the country’s most prestigious medical-care chain, Lanka Hospitals.

These days it’s difficult, particularly for a tourist, to visit the island and not make Gotabaya’s military brass richer.

This even extends to the realm of hairdressing, where in suburban Colombo, the Clippers salon is owned and run by the Sri Lankan Air Force.

Need your poodle trained or transported? Try Sky Pet, a project of Air Marshal Harsha Abeywickrama, whose previous claim to fame was helping to destroy the Tigers’ hand-built bombers.

Elsewhere, the military runs a security company, a hotel chain, a catering service, golf resorts, cricket stadiums, whale watching tours and a zoo on land where Tigers once roamed – one can fly there via a sightseeing helicopter tour also run by the Air Force. In downtown Colombo, a luxurious Shangri-La Hotel is to be built on military land.

Paula Bronstein for The Global Mail

At Thalsevana Holiday Resort, a military venture outside of Jaffna, Sri Lankan soldiers are busy at work.

Outside Jaffna, the Sri Lankan army has developed a seaside hotel on land seized after the war ended. The Thal Sevena Resort was a civil servants’ social club, but has been converted by soldiers into seaside rooms to rent for $US80 a night.

Guests’ whims are attended to by comely Sinhalese staff in saris and sarongs, who are also soldiers: Private Thanuja at reception, Private Rashinda the concierge, Private Jeyaratne changing sheets – all of them supervised by the agreeable Sergeant Ananda and general manager Major Richard Wickremarachchi. Such is the peace dividend at war’s end, Sri Lankan style.